"This is the legacy of our people," my uncle said as we gazed at the pyramids. We were not in Egypt, but rather in the town of Tzintzuntzan, in Mexico's south-western state of Michoacán. The pyramids, or yácatas, looming in front of us were uniquely round and made of volcanic stone – perhaps the most intact relics of the P'urhépechas, a pre-Hispanic indigenous group that once reigned here, but that most people have never heard of. In fact, I'd never heard of them either until a few months ago, when I found out that I was a direct descendant.

Born and raised in California, I grew up unaware of this part of my heritage as it was lost in my family after my grandfather passed away in 1978. My grandmother was left with five kids and no income, but after saving up, she brought my dad and his siblings to the United States in 1983. Under pressure to assimilate, my father disconnected from our P'urhépecha culture, and it was only recently, when I began to be curious about my identity, that I started questioning him about our past. So in 2021, at the age of 31, he brought me to Michoacán for the first time. That's when I met my uncle Israel, and he revealed that not only were we P'urhépecha, but that my great-grandmother, Juana, was still alive and living in the small pueblo of Urén nearby.

When people think about Mexico before Hernán Cortéz, they automatically think about the Aztecs, but what they don't know is that the P'urhépecha existed at the same time – and they were such a mighty kingdom that they were one of the only indigenous groups in Mexico that the Aztecs failed to conquer.

In fact, that's the most common thing people in Mexico know about them, said Fernando Pérez Montesinos, assistant professor of indigenous environmental history at the University of California, Los Angeles. "That's a very usual [way] of referring to the P'urhépechas and their history, but that's because we know that the P'urhépechas were as powerful as the Aztecs," he said, explaining that the Aztecs tried to fight the P'urhépecha in battle, but couldn't defeat them.

Standing tall and strong at 4ft 10in (about 1.4m), my P'urhépecha great-grandmother is an elder of the community and lives in a weathered building made of cement walls and humble commodities. She can speak the endangered language, which is a fading trait in a country where Spanish is the official language. (Out of Mexico's estimated population of 128.9 million, 124.8 million are native Spanish speakers – whereas only 175,000 speak P'urhépecha, and they all live in the state of Michoacán.)

Standing tall and strong at 4ft 10in, my P'urhépecha great-grandmother is an elder of the community who can speak the endangered language (Credit: Stephanie Mendez)

Chatting in Juana's kitchen, I took in everything I could: how she cooks without electricity or a stove; her rows of dishes made from barro (red terracotta clay); and the deep stone pit in the middle of the room where she was preparing a huge pot of nixtamal, corn kernels processed in a specialized way to make tortillas de maíz. Excited about the new knowledge of my ancestry, I asked her where I could go to learn more about my P'urhépecha heritage. She stirred the food and gave my uncle a look of authority as she told him in Spanish, "Take her to Pátzcuaro."

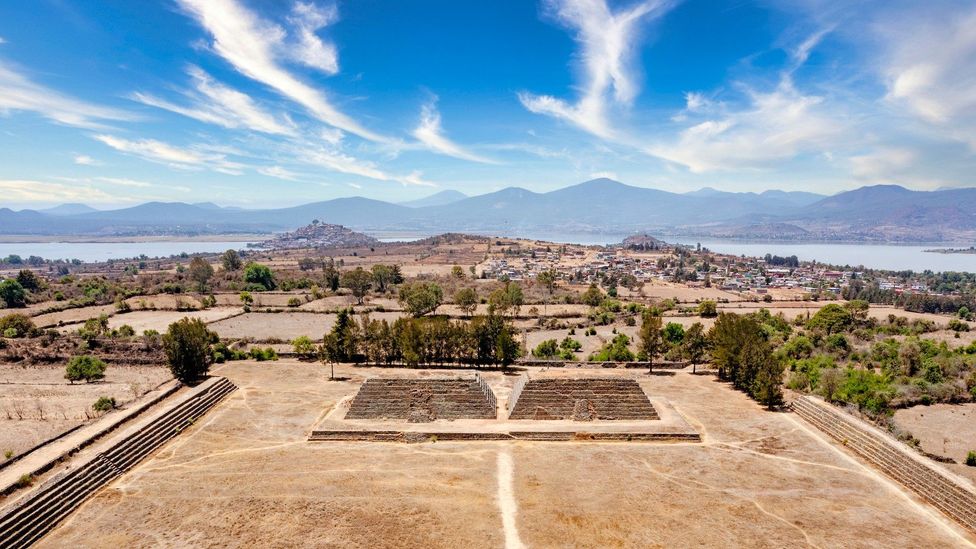

A day later, we were in the Lake Pátzcuaro basin – me, my uncle, aunts and cousins, staring in awe at these monuments that our ancestors had built to honour deities like their sun god, Curicaueri.

Between the 14th and early 16th Centuries, the P'urhépechas dominated western Mexico with an estimated population of more than one million; Tzintzuntzan was their capital, where the irecha, or ruler, lived. (The Aztecs, meanwhile, ruled in Central Mexico, and the P'urhépecha empire prevented them from amassing territory to the north and west.)

The P'urhépecha were one of the only indigenous groups in Mexico that the Aztecs failed to conquer (Credit: Arturo Peña Romano Medina/Getty Images)

According to Jahzeel Aguilera Lara, a geographer and researcher at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, "The yácatas of Tzintzuntzan – the 'place of hummingbirds' – are the best-preserved pyramidal structures in the region. In addition to learning about the P'urhépecha public architecture, [visitors] will also learn about the way in which the P'urhépecha understood the world and the importance that Lake Pátzcuaro had for them."

The empire chose this area for a reason: the basin is home to a colossal lake with several habitable islands, plentiful fish and a surrounding landscape lush with mountains blanketed in pine trees. The area is so spectacular that the P'urhépechas believed the lake was a gateway to heaven.

"This is a very important region for the emergence of the P'urhépecha in the pre-Hispanic state of our history," said Sandra Gutiérrez De Jesus, an indigenous P'urhépecha and professor of Latin American Studies and Chicano/a studies at California State University, Los Angeles. "It was a scenario for gastronomical, cultural and linguistic encounters and exchanges."

But when the Spanish arrived at the Lake Pátzcuaro basin between 1521 and 1522, they captured the P'urhépecha ruler and forced the empire to relinquish its power. Still, as Pérez Montesinos explained, historians consider this transition more peaceful than the siege of the Aztecs. The P'urhépecha people were given more autonomy than their Aztec counterparts, and P'urhépecha elites continued to have influence and authority over the region.

"Nothing could be done without the permission or allowance of P'urhépecha elites," Pérez Montesinos said. "The traditional way to see things is that the Spaniards came and did as they pleased, but what we know now is that the Spaniards always had to ask and negotiate with P'urhépecha elites in order to remain themselves on top."

The traditional way to see things is that the Spaniards came and did as they pleased, but what we know now is that the Spaniards always had to ask and negotiate with P'urhépecha elites in order to remain themselves on top

One example he gives is the Basílica de Nuestra Señora de la Salud, constructed in Pátzcuaro around 1540. "The conventional knowledge is that [Bishop] Vasco De Quiroga built that cathedral, but it was built by P'urhépecha hands," said Pérez Montesinos. He explained that the Spanish did not have to use forced labour to construct the cathedral, as the P'urhépecha community agreed to collaborate and lend their physical labour. "There is this very dominant narrative of trying to downplay the achievements of the everyday P'urhépecha folks by highlighting how it was the Spanish friars who taught them how to make these artisanal works, but in the face of very daunting challenges, the P'urhépecha incorporated new things into their lives to make something original," he said.

As we travelled around the state, I started to see P'urhépecha touches in the architecture. Since Michoacán is rich with oak and pine trees, the P'urhépecha Empire became known for its expertise in wood constructions; their most notable buildings were traditional wooden houses called trojes. After colonisation, the P'urhépecha people incorporated their craftsmanship into the Spanish colonial infrastructure that stands today throughout Michoacán.

Since the P'urhépecha were able to maintain so much autonomy, the three administrative centres of their power – Tzintzuntzan, Pátzcuaro, and Ihuatzio – remained economic hubs during the colonisation era. "I lived in Pátzcuaro during my childhood and it's the most beautiful place to visit for P'urhépecha history, there's no other place like it," my uncle told me.

When we arrived at the town's Plaza Grande, a celebration of P'urhépecha culture was on full display, as is the custom every weekend in Pátzcuaro. Teenage boys performed a traditional dance called Danza de los Viejitos (Dance of the Elderly). They were dressed in white, with colourful handmade serapes and straw-like hats that were covered in vibrant rainbow ribbons. They dawdled with canes and donned uncanny masks of elderly men before breaking into a style of Mexican tap dancing called zapateado. This pre-Hispanic dance was originally performed by the elderly as part of a ritual to the ancient gods, but after the P'urhépecha were colonised, it was used to mock the Spanish, which is why the dancers dress up in comical masks during their exaggerated imitation of old men.

The P'urhépecha community agreed to collaborate with the Spanish to construct the Basílica de Nuestra Señora de la Salud in Pátzcuaro (Credit: Stephanie Mendez)

Even though the empire acquired tremendous power and left behind this incredible legacy, the P'urhépecha Empire has largely been left out of Mexican discourse, overshadowed by the Aztecs. "That has to do more with how Mexican nationalism came out in the 19th and 20th Centuries – everything is based around Mexico City, and the narrative of Mexican identity was built around mostly the legacy of the Aztecs," Pérez Montesinos said. "Also, because there are more narratives of battles, wars and resistance against the Spaniards, there is a lot more material for an epic story, whereas with the P'urhépechas, you don't have the same type of drama."

When I came home from Michoacán, I was a changed person, proud of this newfound knowledge about my heritage, culture and traditions. I was so enthused that I returned to Mexico six months later with my dad and sat down with my great-grandmother to pick up where we left off.

"Can you teach me P'urhépecha?" I asked. Juana pointed past me and said, "He can teach you." I turned around and realised she was pointing at my dad.

"What? You know how to speak P'urhépecha?" I asked in disbelief.

He laughed and said, "That was a long time ago, I used to know, not anymore."

But Juana countered him: "You can teach her," she said. "One never forgets, this is our culture."